bobspirko.ca | Home | Canada Trips | US Trips | Hiking | Snowshoeing | MAP | About

|

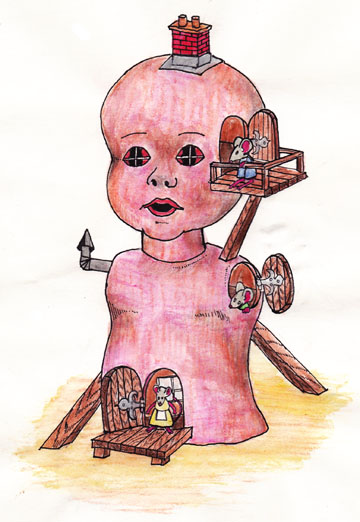

Through the Looking Glass

I saw Dr. Warness in the summer of '75. He greeted me with a smile and a handshake, and after we sat down and talked, I soon felt at ease. This was a doctor who would take his time with me and not prescribe drugs. He agreed with the psychologist's assessment of schizophrenia and suggested I go on megavitamin therapy. Megavitamin therapy, or orthomolecular medicine as it's also called, was developed by Dr. Abram Hoffer, a Saskatchewan psychologist. According to Hoffer, schizophrenics have excessive amounts of adrenochrome, a metabolite of adrenaline that has been shown to cause hallucinations. In the 1950s he demonstrated that large quantities of vitamin B3 could reduce adrenochrome and subsequently eliminate these hallucinations. After treating hundreds of patients, he found that three out of four responded to treatment. (Dr. Hoffer continued advocating the adrenochrome hypothesis until his death in 2009. Further studies have failed to duplicate his results, and currently his treatment is not regarded with any validity.) Not only did I read Dr. Hoffer's book Vitamin B-3 and Schizophrenia, I met him the following year when he was in Calgary and Dr. Warness arranged for me to see him. The visit was brief, but he too confirmed I had schizophrenia. So why is schizophrenia commonly treated with antipsychotic drugs and not vitamin therapy as subscribed by Dr. Hoffer? I asked myself that question decades ago when I was being treated, but now, after searching the Internet, I found an answer in What Really Causes Schizophrenia by Harold D. Foster. Soon after Dr. Hoffer released his studies, Dr. Max Rinkel, a Boston neuropsychiatrist, published a report that disputed Hoffer's claim. Rinkel argued that adrenochrome was not a hallucinogen and therefore Hoffer's results were groundless. After that, interest in the adrenochrome hypothesis died. However, Hoffer countered that Rinkel based his studies on an inert form of adrenochrome that would have no effect. Rinkel conceded the error and released a report admitting his mistake. But the damage was done and Rinkel's correction was overlooked. Dr. Hoffer's adrenochrome hypothesis remains largely ignored today. For the last fifty years, the dopamine hypothesis for schizophrenia has prevailed. It's believed that an excess of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that occurs naturally in the body, causes hallucinations. To block the dopamine, schizophrenics are usually treated with antipsychotic drugs. However, in recent times several factors have been found to challenge this theory. Nonetheless the dopamine hypothesis remains lucrative for drug companies. Antipsychotics generate over $16 billion in worldwide annual sales. Fortunately Dr. Warness treated my schizophrenia with vitamins, not drugs. Because it would take time for vitamin B3 to displace the excessive adrenochrome in my brain, I couldn't expect immediate results. However, I was surprised when my illness became worse, much worse. In the months to follow, not only did my hallucinations become more frequent, they affected all my senses so that I could not trust anything I heard, tasted, smelled, touched or saw. And the strangeness that made the night sky beautiful now pervaded my workplace. The interior of Woolco never looked so good or so surreal. Also my fatigue worsened. This profound fatigue, coupled with my hallucinations, forced me to quit work and go on social assistance. Sadly too, I had a girlfriend at the time and I had to break up with her. It was all I could do to take care of myself. By then I was pretty much a shut-in case, seldom venturing outside. It was January 1976 and I was 25. Still I got worse. Inside my apartment, I now had hallucinations daily, but at least they were usually brief, unlike the interminable weirdness that affected the world outside. For years I had witnessed a nightscape that was becoming increasingly surreal, but now daytime landscapes also appeared distorted. Through the shifting prism of schizophrenia, the scenery outside seemed to change from day to day, as if trees and buildings changed their colours, shapes or sizes, or they moved slightly. Familiar scenery that I once took for granted became difficult to recognize. I hardly recognized my front yard. Day or night, whenever I looked out my front door, I observed a spooky, alien world. Even though I knew it wasn't real, I had trouble dealing with it; I couldn't get my head around the strangeness. It was easier to remain indoors and not even look outside. One night, tired of being shut in, I decided to go for a walk even though it meant facing a freakish world. By now the strangeness of the night had seriously ratcheted up since I first noticed it several years ago. Except for the absence of talking animals, it was an Alice-in-Wonderland moment. Nothing looked like it should; colours and textures were all wrong. The sidewalk appeared strangely soft, so soft that I watched my feet sink into the cement. Indeed, I could feel my feet sink, as if I were walking in mud. But the sidewalk was solid, hard as rock. I was aware that I was hallucinating, but I found the illusion fascinating. I lost interest in the sidewalk when I noticed an extraordinary street lamp. It was emanating rings in alternating colours of purple and yellow. The rings formed around the lamp and then expanded, like ripples in a pond, until they disappeared into the darkness. It was such an amazing sight that I was drawn to stop and stare. I knew it was an ordinary street light and that I must have looked ridiculous gaping at it, but nonetheless I stood there mesmerized as if I were watching a fireworks display. I walked farther up the street to gaze at another spectacular street light, but by then I was growing uncomfortable, as if becoming aware of a bad dream. Suddenly I longed to see and touch real things. I needed to escape back to reality. I turned around and hastened home. The sidewalk that appeared to yield to my footsteps only moments ago now felt firm under my feet. My basement suite was my sanctuary. Inside small, enclosed spaces my surroundings appeared normal for the most part. The floor was solid and the lights didn't radiate yellow and purple rings – except when I turned them off. I was still beset with hallucinations but at least these were usually ephemeral. I smelled perfumes that didn't exist and saw things that weren't there. I heard voices, my name being whispered. One time, while I was lying in bed with my hand relaxed, fingers curled, I suddenly felt a stick in my hand. It seemed so real that I had to look, but of course, my hand was empty. Even among so many bizarre experiences, there was one that stood out: synesthesia. Synesthesia is not a hallucination but a strange condition where one sense is accompanied by a perception in another sense (e.g. seeing sound or tasting colour). My first experience occurred when I went to eat some grapes. I was breaking off grapes from a bunch when my finger touched the end of a broken stem. The stem tasted so bitter, so repugnantly sour, that I reflexively drew back my hand. Incredibly, I had tasted with my finger! It was no hallucination but to be certain, I touched my tongue to the grape stem and found it tasted exactly as what I had experienced with my finger. Another synesthetic experience occurred when I was eating stew. For a brief moment, I saw the food with my tongue, or maybe I was tasting colours, and if that wasn't amazing enough, the stew made a buzzing sound, which too, I heard with my tongue. In my meeting with Dr. Hoffer, I recounted my synesthetic episodes. He didn't say anything to me but later Dr. Warness told me that Hoffer seemed surprised, as if synesthesia is unusual among schizophrenics. I guess my illness came with a bonus symptom. Despite my synesthesia, distortions, hallucinations, euphoric rushes and so on – an amazing constellation of peculiar experiences that schizophrenia threw at me – I managed to take them largely in stride. I had no choice but to accept them as my new reality. Mostly I shrugged them off, but sometimes I got a kick out of them. That's not to say I was never surprised; they were all surprising. Fortunately I didn't trust my hallucinations for that would have left me delusional: thinking or behaving irrationally because I believed my hallucinations were real. Instead, I recognized and tagged them as hallucinations almost as fast as they assailed my senses (that's not to suggest I hallucinated constantly; at the most it happened only a few times a day). And since I was able to separate surreality from reality, I managed to keep my cool. I didn't become moody, catatonic or socially withdrawn. Nor was I paranoid or delusional. I think it would have been easy to become delusional had I trusted my senses. Take for instance just one sense, my sense of taste. Sometimes my food tasted odd, not bad-tasting, just unexpectedly and totally different. Had I complete faith in my sense of taste, then I might have concluded that my food had been altered, that I was being poisoned. The fact is, all my senses including taste were at risk of being distorted. Just as familiar objects could look altered, familiar foods could and did take on unusual flavours. But I knew that so when my meals tasted funny, I wasn't tricked into thinking I was being poisoned. I was just hallucinating. I just didn't take my hallucinations seriously, not for more than a couple of seconds, anyway. I likened it to having a distortional filter. My surroundings hadn't changed and I was certain my mind was still sound, but sometimes information from my surroundings was diverted through this filter where it was warped mildly or even severely before reaching my brain. Even then, my hallucinations were either benign or enjoyable, at least in small doses. Only later, which I will come to, did I realize a hallucination could be terrifying. Since I was aware of what was happening to me and never doubted that I would overcome my illness, I accepted having schizophrenia. I saw it as a fallibility of my senses, not my mind. I never thought myself mentally ill and I doubt if anyone perceived anything was wrong with me. Nor did I feel ashamed of having schizophrenia. Indeed, I delighted in relating some of my fantastic experiences to friends, family and even strangers. I recall one time when I related a hallucination as it happened. I was playing cards with two of my buddies when one of them dealt a card that came spinning my way. As I watched, the whirling pattern on the back of the card suddenly transformed into a 3D image of a vortex – like a tiny tornado – that went right through the table. It was only a hallucination, but I thought it hilarious and I laughed. I tried to explain it to my friends, but they only looked at one another. Schizophrenia is no laughing matter, of course, and I took my illness and my recovery seriously. |