bobspirko.ca | Home | Canada Trips | US Trips | Hiking | Snowshoeing | MAP | About

Bio PrefaceLong before I set foot on a mountain or even aspired to hike, I was thrust into truly strange circumstances. Although these circumstances have nothing to do with my outdoor adventures, they led to events more fascinating than any of my trip reports. However, some readers may think these events are too remarkable, even unbelievable, and I'm concerned I may not be taken seriously. Some accounts will surely strain credibility. But more than anything, I want my writing, whether here or in my trip reports, to be trusted and not dismissed as a product of imagination, fabrication or some delusion. Incidences portrayed here in my autobiography, as improbable as they may appear, occurred just as I have described them. I pride myself in thinking and writing objectively, and I take to heart a passage from William Zinsser's book, Writing About Your Life: “To write about your life you only have to be true to yourself.”Bob Spirko |

Photo from the Internet |

Signs of Trouble I was in my late teens when the night sky changed. It probably happened gradually over time, nudging the edges of my awareness at first before capturing my complete attention, but when I took notice, the change was startling. What used to be a typical star-filled sky became an extraordinary spectacle. Stars that used to twinkle now dazzled as if far brighter, clearer and more beautiful than I had ever observed, a sight so amazing that I often stood spellbound whenever I stepped outside on a clear night. And it wasn't just stars. All nighttime scenery, even ordinary street lamps and whatever surfaces their light fell on, appeared unusual and alluring. The night sky hadn't changed of course, nor did I believe that my night vision had somehow improved. I wasn't seeing better, just differently; nightscapes were much prettier than they used to be. Although I wondered why and was sure I was seeing the night sky differently than anyone else, I could see no harm in it and I rather enjoyed it. I could not have guessed that it meant trouble, serious trouble. Before the night sky changed, my life was normal enough. My father was a welder and my family – my parents and two brothers – lived modestly in Fort Erie, Ontario, a border town across the Niagara River from Buffalo, NY. Since our home sat on the edge of town near the woods, and since I was adventurous, I often took to exploring the forest, catching frogs and snakes, and climbing trees. Those boyhood interests gave way to academic pursuits when I entered high school and my attention turned to math and science. In 1969 after I finished grade 13 (the extra year was available in Ontario until 2002), I looked forward to studying math and computer science at Waterloo University. Back then, of course, computers were slow and ponderous. A single computer might fill a large room yet have only one megabyte of memory. There were no computer terminals; programs were typed on punch cards, one line of code per card. I enrolled in the cooperative program: four months of school alternating with four months of study-related work. It would take longer to get my degree, but the work would help pay my way through university as well as provide valuable experience. Ambitious and studious, I wanted to be a computer programmer. However, that never happened. After entering university, I became uncharacteristically apathetic. I made poor grades in school, and on my second work term I made an error that cost a company a million-dollar contract. I barely made it through my first year of university only to fail my second. It was odd that I should lose interest in school, almost as odd as the unnatural brilliance I still saw in the stars at night. Yet stranger things were about to befall me. In 1972 I dropped out of university and moved to Niagara Falls, Ontario to work as a milkman. Aside from paying the bills, driving a milk truck allowed me to meet people, especially girls. I had lost my zeal for school, but I was still attracted to the opposite sex. In fact, I was on a date when I had my first mind-blowing experience. It was the weirdest thing. One minute I was walking in a mall and next I was down on my knees, overwhelmed with pleasure. It wasn't drugs that led to it, but a storefront. Not just any store, but a shiny, one-of-a-kind store with glass and chrome just like the one I had seen in Buffalo. Such a unique store couldn't possibly exist elsewhere, or so I thought, but it did and it was here in a mall in Niagara Falls and I couldn't comprehend it. I was confused. Was I in Buffalo or was this the same store in another city? My mind reeled as I tried to sort it out and that's when it hit me. A sudden, warm rush ran up my spine and exploded in my head. It was an intense pleasure, an ecstasy so powerful that I fell to my knees. For a couple of seconds I was oblivious to all else. Then the mysterious euphoria left me and I became aware that I was kneeling on a mall floor with a girl standing next to me. As I got to my feet I wondered what to tell my date, and for that matter, what to tell myself. I couldn't account for the head rush or whatever it was. In all my 22 years I had never experienced anything like it. Whatever it was, I couldn't even guess. Months went by and the body rush incident was nearly forgotten when another oddity arose. I had a girlfriend now and after getting together with her, I dropped her off and kissed her goodbye. Nothing unusual about that except our kiss didn't end. That is, as I drove away I could still feel her lips pressed to mine. The sensation was so real, so tangible, that it was impossible to ignore, and it wasn't just peculiar, it was annoying, a distraction. I tried rubbing my lips to release that kiss, but those phantom lips remained locked on mine. An hour must have passed before her kiss finally disappeared. Being more pragmatic than romantic, I tried to come up with a rational explanation but couldn't. So I shrugged it off as a harmless mystery. I never imagined there would come a time when all my senses would go haywire, when not everything I saw, heard, felt, smelled or tasted was real. Then with the advent of stores selling cheaper milk, my job as a milkman ended. I couldn't find work in Niagara Falls, so I moved to Toronto. There I took on two jobs. In the evenings I sold betting tickets at a horse racing track, Greenwood Raceway (now defunct), but during the day I worked full time driving a truck for Canadian Linen. The latter entailed dropping off clean articles such as uniforms and towels, and picking up soiled ones. Months passed and I became comfortable living and working in the big, bustling city of Toronto. Nightscapes still appeared strangely resplendent, but everything else was normal – until I ran into the girl who made a face. It happened while I was working, when I stopped at a fitness centre on my route. The centre went through a lot of towels, which, after being used, were tossed into large canvas bags. Since the used towels were damp, the bags were quite heavy. Helping me with the bags that day was a young, pretty girl who worked behind the counter. She tried lifting one of the bags, but it proved too heavy for her. As she struggled with it, her face flushed and contorted in effort. Yet she seemed amused, as if she found it funny that she couldn't lift a bag of towels. As a result, her face portrayed conflicting expressions, at once both straining and smiling. For some reason, her contrary image seared into my mind, and like the storefront episode in Niagara Falls a year earlier, it confused me and caused my brain to burst with pleasure. But not right away. I threw the towels in my truck and drove away. As I negotiated the busy streets of downtown Toronto, I thought about the pretty girl lifting that heavy bag. However, when I pictured her straining, smiling face, something extraordinary happened. In my mind and of its own accord, her face changed into bright colours and then, like stirring colours in a paint can, they swirled. Suddenly a warm rush ran up my spine and exploded in my head. If I hadn't been sitting down the ecstasy probably would have brought me to my knees as it did before. For a few seconds, exquisite pleasure flooded my mind, obliterating all thought and awareness. When I recovered, I couldn't resist trying it again. After checking to make sure I hadn't lost control of my truck, I again pictured her face and again it melted into colours and climaxed in euphoria. And I kept doing it. The euphoric episodes reminded me of an experiment done with rats in the 1960s, something I remembered from my psychology classes at university. The brains of rats were wired so that whenever a rat pressed a bar, it triggered the animal's pleasure centres. Such was the reward that the rats hit the bar hundreds of times a day. I was like one of those rats, stimulating pleasure receptors in my brain over and over. Instead of pressing a bar, though, I was conjuring an image in my mind. And instead of being in the safety of a cage, I was driving down Highway 401, one of the busiest thoroughfares in Toronto. But nothing was more important than that rush, not even the risk of getting killed, so I kept doing it. Fortunately the effects diminished with each episode and I calmed down before I crashed. Even so, for the rest of the day, but less frequently, I continued to induce decreasingly smaller rushes by picturing the girl's straining face. By the following morning, the effect was reduced to a buzz before it disappeared. The entire experience was bizarre, almost alarmingly so. By merely picturing a girl's face I had become extremely high. I couldn't begin to understand it, nor did I tell anyone about this or my other extraordinary experiences. Who would believe me? In 1973 I had had enough of Toronto so I moved back to my hometown, Fort Erie. I took a job at Fleet Manufacturing, an aircraft parts factory that also employed my father and brother. I worked as an expediter, ferrying parts from one department to another. I settled into a normal life, normal except for the alluring night sky and my unusual degree of apathy. I also had some delightful head rushes, this time triggered by music. These were not the sensations-to-die-for like I had before, but they were extraordinarily pleasant. For instance, I got a rush when I first heard a song whose name I can't remember. Certain notes sent me reeling well beyond anything attributable to mere listening pleasure. At the time, I was at a bar with a friend, sipping a coke (I don’t drink). Caught off guard, as if I were having an unexpected organism in a public place, I was surprised and alarmed. I tried to stifle my reaction to the sudden, explosive euphoria, but my eyes betrayed me, flying open. However, my friend never noticed and I was glad not to have tried explaining it. However, I was becoming concerned with a real problem that appeared to be worsening. Since leaving high school, I had been having bouts of fatigue. For hours or even days at a time, I felt unaccountably tired. When it happened at work, I had to struggle to make it through the day. Still, most days I was fine, so I didn't worry about it much. When I felt good, I was bursting with energy. I bought a bicycle and went on long rides. I especially enjoyed cycling along the Niagara Parkway, a scenic road that follows the Niagara River from Fort Erie to Niagara Falls, about a 100 km round trip. One day I decided to press farther, past the Falls all the way to Queenston Heights. I was full of vigour, zipping along and almost at my destination when I hit a patch of gravel. I slid out of control and slammed face-first into the road. Gravel sliced my legs, shoulder, hands and face. The accident left me bleeding in several places. After getting up and looking around, I spied a policeman sitting in his vehicle down the street. I limped over to him and calmly asked for a ride to the hospital. I must have looked a fright for in his haste to come to my aid, and much to my amusement, he tumbled out of his car onto the ground. The cop drove me to a hospital in Niagara Falls. I was covered with so much blood and dirt that the hospital staff asked me to bathe in a bathtub. Afterwards, they treated my cuts and scrapes. They swathed my hands in bandages, rendering them nearly useless. (I had to take a week off of work; never again did I ride without cycling gloves.) My worst injury was to my face. Before suturing 14 stitches for a laceration in my cheek, they removed a stone the size of a pea. After I was released from the hospital, my father picked me up and brought me home. They say that after you've fallen off a horse, you should get back on. Although I had trouble holding the handlebars with my bandaged hands, I went for a short bike ride. That was in the summer of '74. Years would pass before I would again have such vitality. |

|

|

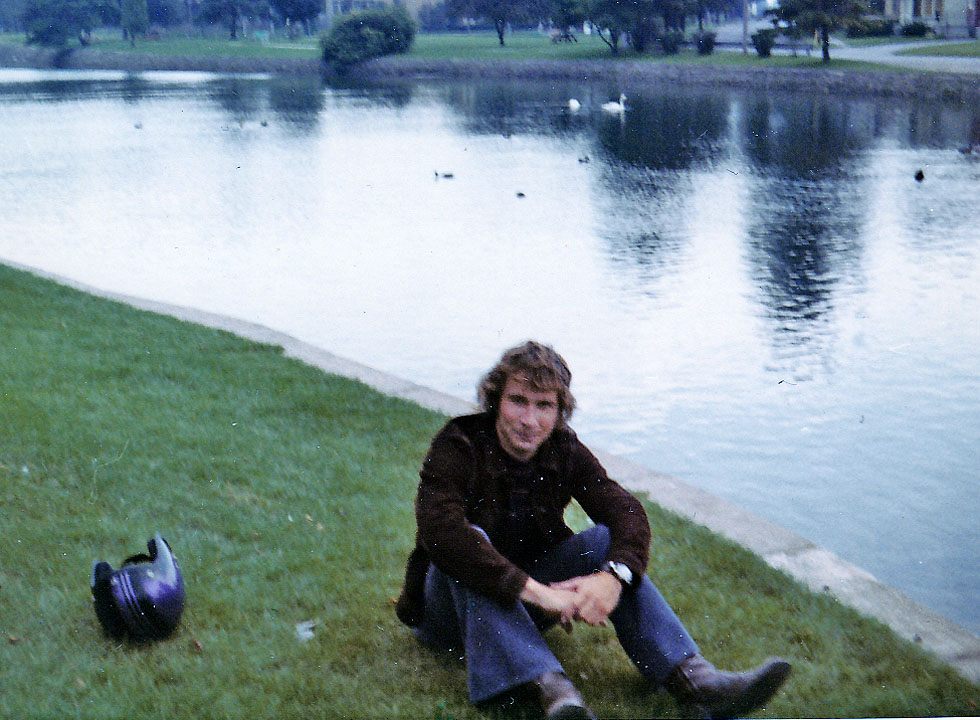

After a motorcycle ride (1974) |

|